pardes gayaan pardesi hoyaan

teriaan nitt vatnaan val loran

jogan kamli karke sutt gayaan

baithi kakh galiyan de bhoraan

chaal piya di aisi niraali

jivein pehlaan payiyaan moraan

yaar fareed main kaafir howan

je mukh sajna walon moraan

You went far away, became a stranger

I constantly remember you here

You made me crazy, then threw me away

I can't find anything on the streets

My love walks so beautifully

like a peacock dancing

I would be called an outcast

if I turn away from my love

kook dilan kaddi rabb sunesi

ehna dard mandan diyan aahin

tailan baaj na ballan mashaalan

kitte dardan baaj na aahin

lokan diyan jhokan payiyaan wasdiyan aayiyaan

kaddi saddi vi wasdi aahi

ki hoya tussan bolan chaddeya

assan vekhan chaddna naahi

Someday God will hear my cry

Such are the sorrowful sighs

without oil mashaals don't burn

there are no sighs

so what if you don't talk to me

I won't stop

aa kaaga tainu churiyaan paawan

kaddi sadde vi baith banere

de paigaam koi sajna waala

ve main shagan manaawan tere

aa ke baith banere sadde

shayad aa jaan saajan mere

addiyaan chuk chuk yaar fareeda

raah takkan main shaam savere

come crow, sit on my window sill

I will make you a sweet dessert

give me some message from my love

I will celebrate your coming

come and sit on my window sill

perhaps my love would also come

I am standing on my heels O Fareed

looking for you on the way all day

avein bol na banere utte kaawaan sajna nahi aaona

chete haar shingaar na mainu

bhul gayiyaan sab sakhiyaan

har dam ohdi raahwan vekhan

eh dukhiyaariyaan ankhiyaan

tak tak ohdiyaan sunjhiyaan raahwan

hun nazaran vi ne thakkiyaan

saadik sajna nahi aaona

assi pher vi aasaan rakhiyaan

yaad ohdi vich chham chham raunde nain ne dardan maare

kulli yaad bhulaayan vi na kite lakh main chaare

mukh partaake tur gaya maahi karke jhoothe kaare

saadik rehndiyan dinne udeekan raat nu ginn diyan taare

avein bol na banere utte kaawaan sajna nahi aaona

payiyaan kadon diyan sunjiyaan raahwaan sajna nahi aaona

dil mere nu wad wad khaawe

kaanu evein boliyan paawe

chup kar ja tainu main samjhaawan

sajna nahi aaona

na tu boli bol banere

mud ja tarle paawan tere

na jhoothiyan de sadaawaan

sajna nahi aaona

sochan de vich dil ghabraaya

'Saadik' mud watani nahi aaya

aaona howe te dasse sarnaawa

sajna nahi aaona

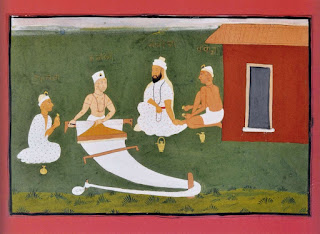

Raag: Bhatiyar

Thaat: Marwa

Time: Dawn

Notes (Swaras): Komal Rishabh, both Shuddha and Tivra Madhyam. All other notes are Shuddha.

Raag Bhatiyar is a morning Raaga. An offshoot of Thaat Marwa, Raag Bhatiyar has a strong emotional undercurrent – something you might not expect from a morning melody. The Raaga begins with all Shuddha notes; Sa-Ma-Pa-Dha-Ni.. all pure just like the morning dew. It almost lulls you back into that tasteful sleep you just woke up from. You sit back enjoying a cup of hot tea with the newpaper lying on the table in your front and that is when Bhatiyar takes a wild turn while on Nishad, skipping the higher Shadja and falling upon Komal Rishibh revealing a deep sorrow that has always been lingering beneath the seemingly serene surface of the pure notes of the Raaga. In the audio clip, focus on the connection between Shuddh Nishad and Komal Rishabh while Mashkoor Ali Khan sings the words ‘…Murata Murari’.

But after that unexpected emotional burst, just when you begin to experience melancholy, Raag Bhatiyar returns to its jovial mood with sequences like (Sa) Dha-Ni-Pa, Pa-Ma-Pa, Ga-Pa-Ga-Re-Sa and brings the smile back on your face.

Raag Bhatiyar is not an easy Raaga to perform what with its intricate and complex tactics. Only an acclaimed artiste can unfold this Raaga for your experience and only an acclaimed artiste can reveal the essence of this Raaga. Raag Bhatiyar is immensely pleasing and peaceful to ears. Raag Bhatiyar possesses healing qualities; it can effectively console an aggrieved mind and calm your soul.

Everyone wonders: Why do good things happen to bad people? Why do fortunes never come the way we desire? Why are we unhappy? Why do we have to marry and produce children? From these questions come our understanding of the world.

The word ‘why’ is translated as ka in Sanskrit, the sacred language of Hinduism. Ka is the first consonant of the Sanskrit language. It is both an interrogation as well as an exclamation. It is also one of the earliest names given to God in Hinduism.

During funeral ceremonies, Hindus are encouraged to feed crows. The crow caws, “Ka?! Ka?!” It is the voice of the ancestors who hope that the children they have left behind on earth spend adequate time on the most fundamental question of existence, “Why?! Why?!”

In mythology there is a crow called Kakabhusandi who sits on the branch of Kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree. The tree fulfills every wish but is unable to answer Kakabhusandi’s timeless and universal question, “Ka?! Ka?!”

The question need not be why. It can be who. Who is responsible for giving me this life? Or it can be what. What can be responsible for giving me this life? From the root ‘ka’ comes the various interrogatives that are parts of Hindi, a modern Indian language which has Sanskrit as one of its major tributaries: what or kya, who or kaun, why or kyon, how or kaise.

The 19th century European Orientalists presented Hinduism to the world as a religion when they discovered in Vedic scriptures an underlying thought that unified the diversity of Indian customs, hitherto deemed pagan and heathen. But the religions they were exposed to, such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, tended to be prescriptive, with very clear rules and codes of conduct. Vedic is more reflective than prescriptive. Reflections are timeless and universal while prescriptions are contextual specific to communities of a particular place in a particular period. Many therefore do not like viewing Hinduism as a religion and prefer to see it as a way of life. Reflections begin when we ask the question, ‘why’. There is no hurry to conclude or to cling to a convenient answer. The exploration continues for as long as it takes, until one is satisfied.

In India, the answer offered for the circumstances over which one has no control is karma. Actions in our past lives determine the fortunes and misfortunes of this life. We thus are made responsible for our bodies and our families. Actions performed in this life will determine our body and our family in our next life.

Is this true? No one knows. But the consequences of believing it are far-reaching.

Belief in rebirth puts the responsibility of our life squarely on our shoulders. For actions that we committed we have been given the life that we are living. We may not remember those past actions, but we are responsible for the present moment, nevertheless.

Mandavya one day found himself being arrested and brutally punished by the king’s guard for a crime he did not commit. “Why?” he asked Yama, the god of death. Yama looked at the book of karma and replied, “As a child you tortured insects. This is the reaction of that action. What seems unfair in one lifetime, becomes fair when one considers several lifetimes.”

Who then is responsible for my life and my fortunes and misfortunes? I am. This means I cannot blame anyone for my misfortune, not my parents, not my circumstances, not my DNA, not even God.

Karma is loosely translated as fate.

Only humans can ask these questions and reflect on life. Ka ?! Because humans have an evolutionary advantage. We are blessed with the neo-frontal cortex, the part of the brain behind the forehead. This is the human brain located on top of the animal brain. It allows us to do what no other creature can do: it allows us to imagine!

Hindus smear their forehead with ash or sandal paste or red kumkum powder. It is the dot known as bindi on the forehead of women. It is the vertical and upwardly directed line known as tilak on the forehead of men. It is a ritual through which voiceless ancestors are telling the children they left behind on earth: use this unique organ behind your forehead. It is what makes you human!

Only humans can imagine a world that is distinct from reality. We can compare reality with an imagined reality and therefore wonder why reality is the way it is. We can imagine being born in another family and wonder: why was I born in this one? We can imagine being born with a taller or shorter, fairer or darker, body and wonder: why was I born with this one? Imagination propels us towards the question: Ka?!

Imagination is translated as manas. Humans possess manas. Therefore the human race is the race of Manavas, those who can imagine. The leader of the human race becomes Manu. Manas also means the mind, the mind which can take flight like a bird or slither like a serpent, and look at the world both broadly and narrowly, reflect on things here and not here, exist both here and now and also over there in the past and over here in the future.

While the human brain enjoys imagination, it does not enjoy introspection. Pondering on questions and seeking answers needs a lot of energy in the form of glucose. Glucose is a precious body fuel. The body would rather conserve this energy for moments of crisis. Naturally, though humans are the only creatures with the wherewithal to introspect, human physiology is geared to block this process. It takes a great amount of will to overpower this block and introspect and seek the answer to Ka. In a way, this is very similar to exercise. It demands huge will power. Few indulge in this quest. Fewer still are naturally inclined for it. The one who indulges in this quest is called a brahmana.

The word brahmana is derived from the Sanskrit root ‘brh’ meaning ‘to grow’ and ‘manas’. All living creatures grow physically after birth. But there is a limit to this physical growth. Humans are the only creatures capable of limitless growth. Why? Because of manas. The possibilities offered by imagination and introspection are infinite. The one who uses these infinite possibilities to discover Ka therefore becomes brahmana, the one with expanded imagination.

From the root ‘brh’ also comes the name of God. Not one, but two. One is Brahma. The other is brahmn. Notice the difference in spelling and the use of capitals. Brahma is pronounced by laying stress to the latter vowel; brahmn is pronounced laying stree to no vowel; brahmana is produced by laying stress to the first vowel and the last consonant. Brahma is a proper noun, brahmn is not considered a noun while brahmana is a common noun. Brahma is a finite personality, brahmn is an infinite abstract notion. The brahmana is the one who seeks to move from the finite to the infinite, from the form to the formless, from Brahma to brahmn.

Every human being is a Brahma. The day he seeks to decipher the puzzle of Ka, the song of the crow, he becomes a brahmana. Every human being has the wherewithal to realize Ka, hence brahmn. Brahma is who we are while brahmn is who we can become. One transforms from Brahma to brahmn, from finiteness to infiniteness, from restlessness to repose, from anxiety to self-assurance, by using the neo-frontal context to imagine and introspect. Bowing to deities in temples and fellow human beings is to remind those before us of the Vedic maxim, “Tat Tvam Asi,” meaning ‘that’s what you are’, you are Brahma who is capable of realizing brahmn. That’s what I am too, hence “Aham Brahmasmi.”

Singing oneness!

Singing oneness!